A Young Henry Ford

A Young Henry Ford

1832 Samuel and George Ford arrive from Ireland and settle in Dearborn Township

A New World Beckons

Michigan was a crude world but one of promise to Samuel and George Ford, former tenants on the estate of Madame, village of Ballenascarthy, County Cork, Ireland. It was 1832 when they both arrived from Europe to take up land in Dearborn Township. Behind them in Ireland, their widowed mother, Rebecca Jennings Ford and their older brother John maintained the family tenancy. Samuel and George soon began the continuous battle with the elements, duplicating the experience of all pioneer farm families as they carved a home from the virgin forest.1847 John and William Ford, grandfather and father of Henry Ford arrive from Ireland and settle in Dearborn

Samuel Ford died in 1842, but his grown sons carried on the family work, and along with George Ford had become well established by 1847. Cattle, cleared fields planted with crops and rude but substantial homes testified to their industry and persistence. Michigan had prospered with them, rising to a sovereign state but ten years before it was now dotted with small settlements. Detroit had nearly 20,000 people and a thriving waterfront industry was laying a foundation for the future.

Reports from America of personal prosperity and the taming of the wilderness became ever more enticing to the family in Ireland. At last in 1847, the seventy-one year old Rebecca Ford with her married sons, John and Robert, set sail for the new world. The voyage proved especially tragic to John and his seven children, for Thomasine Ford, wife and mother, did not survive the trip. The saddened family, leaving Robert Ford and his family in Canada, continued on to join their kin in Dearborn Township where their sorrow would be eased by the hard work of a new world.

The new arrivals were welcomed and given a home until they could make one for themselves. John was not long in locating Henry Maybury, an old acquaintance from Ireland, who was willing to sell eighty acres of his land to the newcomer. On January 15, 1848, John Ford became a landowner in Redford Township and began to clear the trees for his home, which was to stand on what is now the corner of Joy and Evergreen Roads.

John and his family still faced primitive conditions but the area had improved rapidly since the year of George and Samuel's arrival. Not far away was the flourishing town of Dearbornville with a Methodist church, a sawmill, flourmill, seven stores, two smithies, an iron foundry, railroad stop and some sixty families. To the south on what later became Warren Avenue the sturdy Scotch Settlement had erected a schoolhouse (1839) on the northeast corner of Richard Gardner's land. Within the surrounding area, the population numbered almost 5,000. The frontier period was drawing to a close.

Aided by his sons, John Ford began the arduous task of clearing his land. He and his oldest son William also found employment for their skill with tools in the construction of the westward extension of the Michigan Central Railroad. The money from these efforts was used to raise the mortgage John had taken to purchase the farm and to carry the family expenses until their land could make them independent.

1847 "Mr. Ford's Grandfather"

This copy of a tintype (ca. 1850 -55) was copied at the request of Henry Ford in 1924, and labeled "Mr. Ford's Grandfather." It is quite possible that this is Patrick O'Hern.1858 William Ford becomes landowner

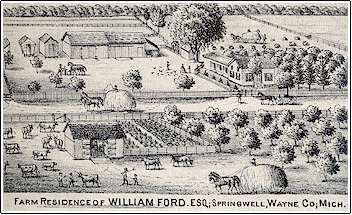

William Ford was a wiry young man of medium height, with high cheekbones and firm bone structure that were characteristic of the Ford family. Born and raised on an Irish tenancy, he had a deep respect for the independent life of the landowning farmer and his persistent industry was directed toward the time when he himself could become a landholder. By 1858, he had saved enough to realize his ambition. On September 15 of that year, he purchased the southern half of his father’s farm for $600, while his brother Samuel bought the northern half for the same sum.

In addition to his own farm, William Ford worked for (or with) Patrick O’Hern, a prosperous farmer whose ninety-one acres straddled the junction line between Dearborn and Springwells Townships. O’Hern like the Fords had emigrated from County Cork (1830) to the Detroit area where he married Margaret Stevens on July 15, 1834. Beginning in 1841, the O’Herns purchased land in Dearborn and Springwells Townships and made their home at what is now the corner of Ford and Greenfield Roads.

1861 William Ford weds Mary Litogot

While at the O’Hern home, William Ford met Mary Litogot, an attractive, dark-eyed young woman. After she was orphaned by the accidental death of her father, Mary Litogot had found the love and affection of true parents in Margaret and Patrick O’Hern. The friendship of William and Mary ripened into romance, fulfilled by marriage on April 25, 1861. Once again, former friends of Ireland shared in the Ford happiness as Thomas Maybury opened his home for the wedding ceremony.

The newly wed couple moved into the rude log structure of the O’Hern home, while William planned and constructed a new house to be occupied by both families. Later in 1867, the entire holdings of the O’Hern family were transferred to William and Mary Ford.

In 1861, the two families moved into their new, seven-room home, an imposing house for its day, to which four rooms would be later, added. William Ford had become the head of the household with a large and profitable farm under his supervision. Soon his appointments as deacon of the church, member of the school board and justice of the peace would recognize him as a valuable member of the community.

1863 Henry Ford is born

July 30, 1863

It was this background of relative prosperity and mutual affection that was to nurture a boy whose name was to become a household word throughout the world, for it was here in these peaceful surroundings that Henry Ford, son of William and Mary Litogot Ford, was born on the early morning of July 30, 1863.The Early Years

Henry Ford was fortunate in his surroundings and early life. His father was a prosperous, respected citizen of the community, and he grew to maturity in the longest era of peace the young republic had known. Michigan, with the rest of the country was to begin a period of industrial expansion unequaled in history. Boys were to leave the farms as part of a growing urbanization that would not be checked until mass- produced automobiles made possible the suburban movement.

In 1863 these deep and swift running currents of change were still but a springhead, and the childhood memories of Henry Ford were of a simple life. Years later (1913) Henry Ford was to write that his first memory was of his father showing him and his brother John a bird's nest under a fallen oak some twenty rods east of his home. The awakening of the child to the beauty of nature was not accidental, and he was to see his father turn his plow from the furrow to leave a bird's nest undisturbed. In one of his many jot books, Henry Ford had written his own story of this incident. Grandfather O'Hern (as he was called) also taught the child the simple pleasures of nature-the names of the flowers that bordered the field, the trees in the woods, and the feathered and furred creatures that made their homes in the fields and forests near the homestead. A love of nature was a central part of Henry Ford's being throughout his life.

1871 First Day of School

January 11, 1871

Mary Ford, despite the burdens of a growing family, (John 1865, Margaret 1867, Jane 1869, William 1871 and Robert 1873) found time to instill in the child her own sense of cleanliness and order. She also taught him to read, and when on January 11, 1871, Henry walked 1 1/2 miles to the Scotch Settlement School for the first time; he had already mastered the first McGuffey Reader.

Henry was not a “book-minded" scholar. His interest in mechanics was predominant, and machines were to be his library. However he and his seatmate, Edsel Ruddiman, along with the other children in the neighborhood mastered their three r's in the small brick school of the Scotch Settlement.

1873The Miller School

In 1873 Henry changed to the Miller School, about the same distance from his home but located to the west in Dearborn Township. He had become curious about the power of steam, and in what was to be his customary approach, subjected his ideas to a practical test. He tied down the lid of an earthen pot filled with water, placed it over the fire and awaited with interest the results of his experiment. The inevitable explosion not only ruined the pot but scalded the curious boy with boiling water. Reprimanded by his mother, his next experiments were more controlled, one of them being a baking powder can steam engine with a watch wheel for a power drive. This was followed by a larger steam engine made in cooperation with his classmates at the Miller School, but once again a boiler explosion proved the power of steam and burned down the Miller School fence in the process.

Watches next attracted his attention and he soon mastered their intricate mechanisms. He had no tools for the delicate task of watch repairing so he made his own; a filed shingle nail became a screw driver, a corset stay became a pair of tweezers and extra knitting needles were similarly adapted by the skilled boy. The small workbench before the window in his bedroom was soon covered with the watches of his friends and neighbors.

An Interest in All Things Mechanical

Henry's interest in watches was only one phase of his curiosity about all things mechanical, and while watch repairing was always to remain his hobby, he discovered the adult world of steam. In July 1876, Fred Reden brought into the Dearborn area the first portable steam engine Henry Ford had ever seen. Reden encouraged Henry's youthful enthusiasm by letting him fire and run the engine. Years later Henry Ford was to testify that this proved to him that he was by instinct an engineer. The same year, Henry's already aroused interest and talent were diverted into new channels when in company with his father he saw a portable engine moving along the road under its own power. The excited youth jumped off of his father's wagon and was examining this new curiosity before the amused and tolerant man was really aware of what had happened. The intensity of Henry's interest is indicated by his own sharp memory of this incident a quarter of a century later. The youth had seen the possibilities of a self-contained, self-propelled vehicle and the vision of a horseless carriage born at this moment was never to leave Henry Ford until success fulfilled his dream.

Henry's interest in watches was only one phase of his curiosity about all things mechanical, and while watch repairing was always to remain his hobby, he discovered the adult world of steam. In July 1876, Fred Reden brought into the Dearborn area the first portable steam engine Henry Ford had ever seen. Reden encouraged Henry's youthful enthusiasm by letting him fire and run the engine. Years later Henry Ford was to testify that this proved to him that he was by instinct an engineer. The same year, Henry's already aroused interest and talent were diverted into new channels when in company with his father he saw a portable engine moving along the road under its own power. The excited youth jumped off of his father's wagon and was examining this new curiosity before the amused and tolerant man was really aware of what had happened. The intensity of Henry's interest is indicated by his own sharp memory of this incident a quarter of a century later. The youth had seen the possibilities of a self-contained, self-propelled vehicle and the vision of a horseless carriage born at this moment was never to leave Henry Ford until success fulfilled his dream.1876 Mary Ford, his mother, dies..

The same year that Henry Ford first realized he had the instincts of an engineer; the Ford family was shocked by the death of the mother, Mary on May 29, 1876. Her quiet forcefulness and strong moral influence had been the guiding spirit for the entire family. In his own words Henry Ford felt that, "the house was now a watch without a mainspring.

Henry Ford had now lost his strongest tie with the family home. Hating the drudgery of farming, he devoted more and more time to mechanical subjects and finally resolved to become a machinist apprentice in Detroit. Although his father regretted Henry's wish to leave what to William was the ideal way of life, he did not oppose his son's decision. At the age of 16 Henry Ford left his father's farm and traveled to Detroit where he could learn what he needed to know about mechanics in order to fulfill his dreams.